^Flat-tailed horned lizard (Phrynosoma mcallii).

Fish and Wildlife Service Denies Listing

March 14, 2011 - "Flat-Tailed Horned Lizard Does Not Need Endangered Species Act Protection" declared the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) today, after completing an analysis of the Flat-tailed horned lizard’s conservation status. The agency announced that the species does not need protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

"This determination was made because threats to the species as identified in the 1993 proposed rule are not as significant as earlier believed and available data do not indicate the species is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. Threats identified in the 1993 proposed rule included loss and degradation of habitat from agricultural and urban development, OHV use, geothermal energy development, sand and gravel mining, military training activities, and construction of roads and utility corridors, and gold mining."

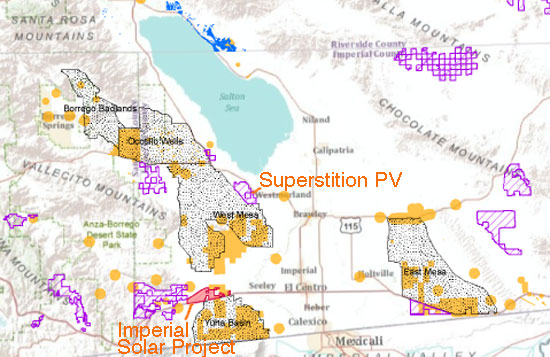

We find this amazing, as large swaths of desert habitat where the lizards are found is slated for solar development in the southern California area of the Colorado Desert, a completely new threat. Imperial Valley Solar Project will block connectivity between two core population areas (Yuha Desert and West Mesa), the project being nearly ten square miles in extent.

In 1997 an Inter-Agency Cooperative Agreement between Federal and State agencies in California and Arizona was signed, and the agencies developed a Rangewide Mangement Strategy to address conservation of the lizard. The Service subsequently withdrew the proposed listing rule in 1997. Since that time the withdrawal has been challenged several times.

Following the most recent challenge to the Service’s determination that the lizard did not need the protection of the Act, a "comprehensive review" of the species’ status was initiated in 2009. Currently, about 457,457 acres of flat-tailed horned lizard habitat is managed by signatories to the Inter-Agency Cooperative Agreement. These lands are divided into five Management Areas (MAs) – the Borrego Badlands, West Mesa, the Yuha Desert, East Mesa, and the Yuma Desert. Additionally, the Ocotillo Wells State Vehicular Recreation Area is a designated research area.

The MAs include core areas to maintain self-sustaining populations of the lizard in the U.S. Although the Coachella Valley population of the lizard is outside of any MA, conservation of that population is being addressed under the Coachella Valley Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan (Coachella Valley MSHCP).

In a bold statement, FWS said: "In reviewing the threats to the species identified in 1993, and any newly identified potential threats, the Service determined habitat loss and degradation largely occurred in the historical past. Although urban development is expected to continue in portions of the lizard’s range, the Coachella Valley MSHCP and the Rangewide Management Strategy provide for the conservation of the flat-tailed horned lizard."

With thousands of acres of solar development pending, we do not see the logic of this statement.

FWS continues, "Energy projects may affect some lizard habitat, but most of the impacts are anticipated to occur outside the designated MAs, and project proponents will be implementing measures to avoid or minimize impacts to the species."

Unfortunately this statement is not correct. For the Imperial Valley Solar Project, no "avoidance" will take place. At first the applicant and California Energy Commission agreed to translocate all the Flat-tailed horned lizards that were encountered during construction. But when biologists raised concerns that past efforts at moving lizards has resulted in very high mortality rates, the plan was abandoned. Instead, lizards will be allowed to remain on the site and suffer the consequences of habitat destruction on more than 6,000 acres. This is not "minimization." In addition, genetic flow and movement between two Maganement Areas will be cut off by the large project.

"The Service’s priority is to make implementation of the ESA less complex, less contentious and more effective. The agency seeks to accelerate recovery of threatened and endangered species across the nation, while making it easier for people to coexist with these species."

This statement seems to indicate the new trend in cutting "red tape" when approving renewable energy projects.

A copy of the final determination is on public view at the Federal Register and can be viewed here – Federal Register. The determination will officially publish on March 15, and will be available at www.regulations.gov. Look for the box that reads “Enter Keyword or ID” and enter the Docket number for this rule, which is FWS-R8-ES-2009-0072. The document will also be posted at http://www.fws.gov/carlsbad.

Jane Hendron, Public Affairs Division Chief Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office Carlsbad, CA

Ph: 760-431-9440 ext. 205

Imperial Valley Solar Project Threatens Rare Lizard

October 10, 2010 - By Laura Cunningham - El Centro, California

Hot mornings walking through creosote desert with seemingly endless dusty horizons, searching the ground for the smallest sign of a rare lizard, are memories I have from the 1990s now awakened by the current plight of the Flat-tailed horned lizard (Phrynosoma mcallii).

Surveying flat desert stretches for the Bureau of Land Management, our team worked early before the temperatures got too hot, scanning the ground for droppings of the lizard, which are filled with ant parts. If we came upon an anthill, we all circled it in widening arcs, looking for the little ant predator. If we were lucky, we found the lizard itself: a 6-inch light tan speckled lizard blending with the sand. The flattish tail is rather long, about half the body length, for horned lizards. A thin dark dorsal stripe extends down the back.

Sometimes a sleeping horned lizard awoke from its sand bed as we walked by, and ran out of its buried position. Long thin legs allow them to escape across the flats more quickly than the usual "horned toad." As the air temperatures climbed to 112 degrees Fahrenheit at 11:00 A.M. we quit, too hot for us, but the lizards hid in the shade of creosote bushes, went underground in rodent burrows, or buried back into the sand. They would come back out in the sunset hours for another bout of feeding on harvester ants on the expanses of shrub-dotted sand flats that are there home.

Flat-tailed horned lizards lay 7-10 eggs in May and June, and hatching occurs in late summer.

Declines Continue

We did these surveys to estimate lizard presence and density because the species was in sharp decline, even back then. The situation has not improved for them.

^Yellow areas are locations of Flat-tailed horned lizards. Core areas for the lizard are in dotted polygons. The Imperial Valley Solar Project will cut off connectivity between the Yuha Basin Core Area and West Mesa.

In a letter from May 2010, Center for Biological Diversity says: "Declines in populations of and habitat for the Flat-tailed horned lizard were noted for decades resulting in a proposed listing of the species in 1993. Several legal challenges have resulted in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service currently reviewing data to determine if the species needs federal Endangered Species Act protection. Threats to the flat-tailed horned lizard are abundant from its small geographic range, it specialized and highly fragmented habitat, its sensitivity to anthropogenic effects, its narrow breadth of diet (almost exclusively harvester ants), and the lowest rates of reproduction of all known horned lizards. All of these factors highlight the potential risk of local and regional extinctions for this species.

"In the more than 15 years since this listing was first proposed in 1993, the threats to the flat-tailed horned lizard have only increased. Clearly the lizard is still in decline, and the Flat- tailed Horned Lizard Management Areas, the voluntary conservation agreement that has been in place since 1997 and the Rangewide Management Strategy (2003) are not sufficient to protect the survival of the species or contribute to its recovery. Moreover, threats to the species are increasing."

Off-road vehicle use in horned lizard habitat has caused declines, Ocotillo Wind Project would disturb more ground over 6,000 acres, and there are at least another five pending right of way applications for both solar and wind projects covering more than 20,000 acres. A new urban sprawl development proposal in Imperial County is the Travertine Point which proposes 12,000 housing units on nearly 5,000 acres adjacent to the Salton Sea. An estimated 43-49% of historical lizard habitat in the United States has been converted to agriculture, urban areas, or other anthropogenic use.

The Flat-tailed horned lizard has almost been extirpated from the Coachella Valley outside of existing conservation areas and the little remaining habitat in Coachella Valley continues to be lost to urbanization. Problems with small reserve size, invasive weeds, loss of sand sources, and boundary effects suggest the current Coachella Valley reserve will not be sufficient to protect the lizards.

New transmission lines, such as the Sunrise Powerlink, and several smaller lines, would also impact lizard habitat. Lines and new fences around solar projects would also provide perches attracting predatory birds such as Loggerhead shrikes and American kestrels, which prey on lizards. Barrows et al. (2006) found a significant increase in predation in their study of boundary effects.

While the Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Rangewide Management Strategy (2003) established Management Areas for the conservation and recovery of the Flat-tailed horned lizard, it fails to include connectivity corridors that will help to ensure genetic viability of the core Management Areas.

The Imperial Valley Solar Project should not be built at this location, as it will destroy 10 square miles of Flat-tailed horned lizards and their habitat. There are agricultural lands that could be retired to save water, disturbed areas, and private lands that can be used for these types of solar projects in Imperial Valley.

Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Habitat

^Anthills in a sandy wash in the western part of the Imperial Valley Solar Project site, indicating good habitat for the Flat-tailed horned lizard.

Desert horned lizards (Phrynosoma platyrhinos) occur on gently sloping alluvial terrain dominated by washes with palo verde and ironwood. Flat-tailed horned lizards occur on finer sands, on more level unbroken terrain in sparse creosote bush - bursage associations, as well as washes. Habitat destruction from urban development and agriculture have taken much of this habitat in Imperial Valley.

^Anthill on the project site, marking the food of the horned lizards. 78% of the lizard's diet may consist of ants.

^Flat-tailed horned lizard.

^Large undercrossing for Coyote Wash along Highway 8.

^Interstate Highway 8 along the southern edge of the project, with the Yuha Desert to the right.

"Highways (even interstate highways) are not total barriers to dispersal. Population genetic theory (supported by experimental data) indicates that if 1 to 10 migrants per generation successfully reach their destination, that is sufficient to maintain connectivity," says Dr. Richard Montanucci, Flat-tailed horned lizard specialist, Clemson University.

^Imperial Valley Solar Project site from Highway 8, not a barrier to lizard movement.

^Sand wash with Big galleta grass (Pleuraphis rigida).

^Connectivity for lizards is easily provided by railroad undercrossings.

^Railroad track along the northern edge of the Imperial Valley Solar Project.

^Flat-tailed horned lizard.

^The Yuha Desert Special Management Area for Flat-tailed horned lizards, just south of the project site, south of Highway 8.

^Flat-tailed horned lizard in hand.

^Flat-tails camouflage with the sand.

^Flat-tailed horned lizard habitat on the Imperial Valley Solar Project site.

^Loose sand coming out of desert pavement badlands.

^Ocotillos (Fouquieria splendens) in a sandy wash in the western part of the project.

^Sand washes that make good Flat-tailed horned lizard habitat on the project site just south of the Plaster City Gypsum plant.

^Winding Shovel-nosed snake track in sand on the project site.

^Western shovel-nosed snake (Chionactis occipitalis). The Colorado Desert subspecies is quite colorful.

^Imperial Valley Solar Project site, May 2010, where sandy lizard habitat meets stony desert pavement.

^Long-horned Flat-tailed horned lizard. A piece of dry skin is shedding off the lizard's back.

^Flat-tailed horned lizard.

^East Mesa, typical habitat where the Flat-tailed horned lizard dwells.

^East Mesa habitat for the rare lizards.

^I found Flat-tailed horned lizards here, in creosote flats.

^Dried Birdcage evening primrose (Oenothera deltoides).

^East Mesa habitat.

^East Mesa habitat for Flat-tailed horned lizard.

Desert Thriving with Life

The Colorado Desert of the El Centro area has many surprises.

^Couch's spadefoot (Scaphiophus couchii), a desert-adapted toad that uses a small "shovel" claw on its hind foot to dig burrows. It also spends the hot days in kangaroo rat burrows, coming out at night in the warm season, and breeding in rain pools.

^Burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), also declining in the Imperial Valley.

^Lesser nighthawk (Chordeiles acutipennis) eggs on the ground under a Bursage (Ambrosia dumosa). These birds do not build a nest but rely on cryptically-colored eggs.

REFERENCES:

Barrows, C.W., M.F. Allen and J.T. Rotenberry. 2006. Boundary processes between a desert sand dune community and an encroaching suburban landscape. Biological Conservation 131: 486-494.

Flat-tailed Horned Lizard (FTHL) Interagency Coordinating Committee (ICC). 2003. Flat-tailed Horned Lizard (FTHL) Rangewide Management Strategy, 2003 Revision: An Arizona- California Conservation Strategy. Pgs. 121.

HOME.....Imperial Solar Project Updates.....Yuha Desert 2015 Update