Fringe-toed lizards

By Laura Cunningham and Kevin Emmerich

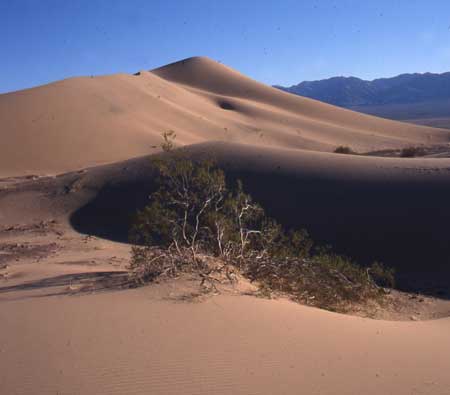

Camping out at Ibex Dunes in southern Death Valley National Park is always a joy. It is a pocket of undisturbed and relatively pristine dunes, home to the interesting Mojave fringe-toed lizard (Uma scoparia). Other dunes are not so protected across the desert: off-roading and blocking of sand corridors by development are some problems.

Fringe-toed lizards are absolutely restricted to fine, wind-blown sand. They avoid coarse sand, or sand infilled with silt and stabilized.

^Ibex Dunes, Death Valley National Park.

^Mojave fringe-toed lizard on the Ibex Dunes.

^These lizards are flattened to help them dive into sand.

^Cryptic coloration aids them in hiding from such predators as lizard-eating Loggerhead shrikes.

From November through February the lizards hibernate buried in the sand or down rodent burrows away from the cold. Females are in breeding condition from May into July or August, and can lay clutches of one to five eggs; after very wet winters they may lay more than one clutch; in drought years they may not reproduce at all.

^Mojave fringe-toed lizard on Kelso Dunes in Mojave National Preserve.

^Ibex Dunes, perfect habitat for fringe-toed lizards.

^Ibex Dunes.

^Scale fringes along the toes help these lizards run on loose sand and dig in.

^An Ibex Dunes lizard dives into the sand and wriggles down in.

^A Kelso Dunes lizard dug in -- only a slight bump in the sand is visible.

^Kelso Dunes specimen, which are slightly yellower in color than the Ibex Dunes lizards.

^Duck-shaped snout for sand-swimming. They have ear flaps to keep the sand out of ear openings.

These lizards eat primarily insects, but in spring will also eat flowers, and seeds when available. Herpetologist Robert Stebbins said they also occasionally predate other lizards.

^Fringe-toed lizard tracks are like little pogo-stick marks in the sand. When going fast they run bipedally on their hind legs.

^Velvety Ibex Dunes hills.

^Mojave fringe-toed lizard hiding under a creosote on Ibex Dunes, showing the black side spots characteristic of this species.

^Ibex Dunes lizard under the cover of plants. OHV activity can wipe out much plant life as vehicles drive over them and crush the plants. Cover is necessary to fringe-toed lizards for cover from predators and temperature control.

^Untrammeled Ibex Dunes.

^Off-roaders at Dumont Dunes.

^Dumont Dunes OHV area, San Bernardino County, California. Plant life has been reduced considerably. We found a few Mojave fringe-toed lizards on the edges of this area.

^Ibex Dunes in a spring wildflower display, free of OHV activity. Insects are humming at sunset, and lizards are out feeding on the bounty.

^Rich dune ecosystem, with abundant tracks of lizards, here mostly Desert iguanas (Dipsosaurus dorsalis).

^Desert dicoria (Dicoria canescens), an annual with a deep taproot accessing moisture in the dune.

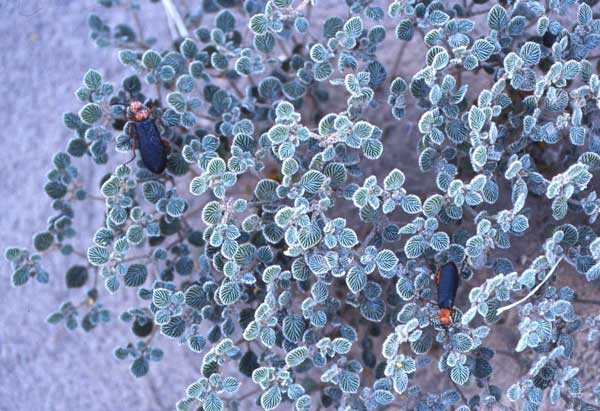

^Tiquilia (Tiquilia plicata), a small perennial on the dunes. Blister beetles (family Meloidae) suck nectar out of the minute flowers.

New Species

Only recently biologists have done genetic work on fringe-toed lizards, and surprises have resulted. The Ibex Dunes population turns out to be part of what may be a new "cryptic species", a northern clade that is only found at dunes north of Baker California: Coyote Holes, Dumont Dunes, and Ibex Dunes. It is cryptic because the lizards look almost identical to other populations in physical form and color, but their genetics are quite distinctive.

We helped out the biologists surveying for these lizards during the genetic work, carried out by the late Dr. David Morafka, then of California State University at Dominguez Hills, and Dr. Robert W. Murphy at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Center for Biological Diversity petitioned to list this Amargosa River Distinct Population Segment of the Mojave fringe-toed lizard as Federally Threatened or Endangered in 2006 (see pdf >>here), and a ruling may be due later this year in 2010. The Ibex-Dumont-Coyote Holes lineage is distinct, and does not interbreed with fringe-toed lizards to the south as at Red Pass Dunes in Fort Irwin Army Training Center northwest of Baker, Murphy determined. The population shows marked genetic differences from other Mojave populations, due to long isolation. Using mitochondrial DNA, Murphy, Morafka, Tanya L. Trépanier identified two distinct maternal lineages that have been isolated since likely the mid-Pleistocene, 500,000 years ago, when orogenic events changed the course of

rivers. These lineages are associated with past and present river drainages that created

the necessary conditions -- sand dunes -- for the lizard to survive, including the

Amargosa River in the north and the Bristol-Lanfair Basin, Pleistocene Colorado River,

Lucerne Trough, and the Mojave River Sink in the south.

Other Mojave fringe-toed lizard populations have gone extinct within recent times. We searched hard for lizards at El Mirage Dry Lake in 2000, following Stebbins' records of this species being present. We found none. The entire area was heavily degraded by OHV activity, and nearby crop-dusting with pesticides in agricultural fields may have eliminated much of the insect foods for these lizards.

Migration Corridors

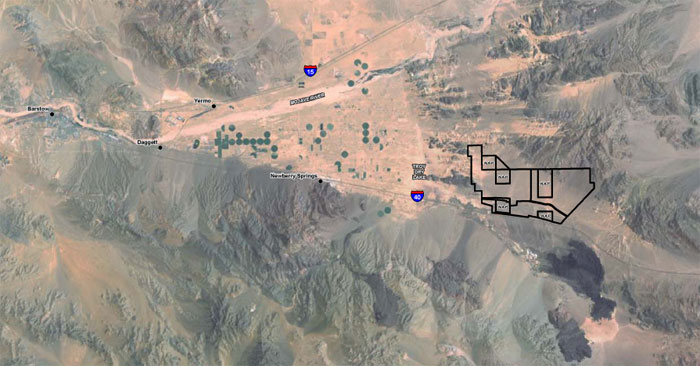

Besides OHV troubles on dunes, a new threat has emerged lately, renewable energy development on wildlands of the desert. Tessera's SES Solar 1 project east of Barstow along Route 66, across the valley from Pisgah Crater, would surround an 11-acre Mojave fringe-toed lizard dune patch with 8,000 acres of SunCatcher solar arrays. The proposal includes fencing in the dune to "protect it."

^SunCatcher technology. (From NREL)

But developers do not seem to understand the dynamic nature of sand ecosystems, and their time-frames of change.

We talked about this concern with Cameron Barrows, Ph.D., at the Center for Conservation Biology, University of California, Riverside, Palm Desert Campus.

He told us of impacts on sand delivery processes for the threatened Coachella Valley fringe-toed lizards (Uma inornata) in the Coachella Valley. The only winds capable of pushing sand come from the west-northwest; blocking that sand flow has severe and immediate negative impacts on the lizards' habitat sustainability.

One way to evaluate the influence of wind in the area of concern is to examine the sand features on the ground (or with google earth). Barchan dunes result from unidirectional winds, as do hummocks only on the down-wind side of shrubs. Star dunes, and the lack of unidirectional hummock development indicates winds from multiple directions. The Kelso

Dunes are great example of a star dune and the features resulting from multi-directional winds.

^Photograph of sand flow from the Mojave River eastward to the SES Solar 1 project site (black outline). Notice the largely unidirectional flow of winds, pushing sand up against the mountain ranges and through basins. Fringe-toed lizards follow such sand deposits through time. (From the SES Solar 1 Plan of Development)

"If winds are unidirectional, blocking sand flow impacts habitat quality and can cause extirpation if the blockage is large enough. If winds are multi-directional, the impacts are less" said Barrows. Aerial photos of the SES Solar 1 project show a unidirectional flow of sand coming from the Mojave River area.

Ice Age rivers and lakes created huge erosional sand deposits, which since the beginning of the Holocene have slowly blown by winds into piles far from these sources. Tessera, trying to minimize impacts of their solar project, claims that sand in the project site actually comes from nearby mountains, in many directions. We believe this is a premature conclusion, and that sand flow appears to come mostly from the west, the Mojave River sand channels. There would be potential for the SunCatcher arrays and associated fencing to block this sand flow, cutting off he renewal of substrate needed for this lizard in the long-term.

^Small sand patch, home of Fringe-toed lizards, in the middle of the proposed 8,000-acre solar development SES Solar 1. The Cady Mountains lie in the distance.

According to the Center's petition to list the northern clade, dispersal of Mojave fringe-toed lizards between populations is poorly studied, but based on observed movements and limited ability of the species to cross unsuitable habitat, it is unlikely that isolated populations interact. They are not found more than 45 meters from fine sand habitat. This high degree of habitat restriction makes the conservation of existing habitat imperative, since the species can not relocate.

Colorado Fringe-toed Lizard

^Algodones Dunes.

^Colorado fringe-toed lizard (Uma notata). This species is similar to the Mojave fringe-toed lizard, but lacks the black throat crescents of that species.

^Prime fringe-toed lizard habitat on the Algodones Dunes in an area off-limits to OHVs. Here vegetation is common, providing food and cover.

All Photographs Copyright 2010 Laura Cunningham except where noted.