<Desert Dandelions and Pincushion.

Location, Location, Location

March 5, 2010 -

The Ridgecrest Solar Power Project, by the German company Solar Millennium AG, takes up a potentially important corridor of Mojave Desert habitat for Desert tortoises and Mojave ground squirrels in the Indian Wells Valley, Kern County, California. The site access road would be from Brown Road, about 2.25 miles west of Highway 395, about 5 miles southwest of Ridgecrest, California. It lies on land managed by Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

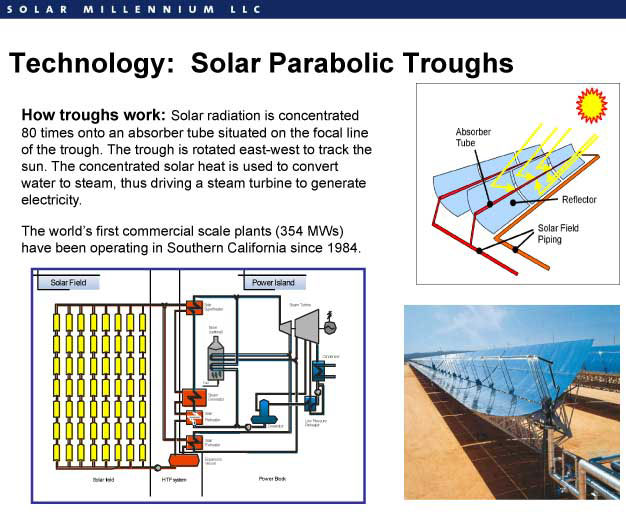

The solar thermal power plant would use parabolic trough technology to generate 250 megawatts (MW) of nameplate capacity (in the real world these types of plants actually produce about 25 - 28% of this [Romero-Alvarez 2007]) split into two solar fields. Being dry-cooled the plant would use 150 acre-feet of water per year, a contentious point with local residents who do not like the idea of an industrial plant pumping their groundwater from Indian Wells Valley Water District in a critically overdrafted basin. Propane would be utilized by the plant for quick startup and heat transfer fluid freeze protection. The project Right-of-Way is proposed at about 4,000 acres, with the facility footprint at 1,448 acres, and disturbance at 1,944 acres. Solar Millennium told the California Energy Commission (CEC) that the numbers shift as they try to redesign. Over the holidays the company changed the footprint to move out of the major wash running through the center of the site, as well as because of concerns with habitat connectivity. But they said they were limited by topographical features, homes, and roads (From teleconference into Renewable Energy Policy Group Meeting for January 22, 2010 (http://www.energy.ca.gov/siting/meetings/2010-01-22_meeting/2010-01-22_Agenda_Project_List.pdf).

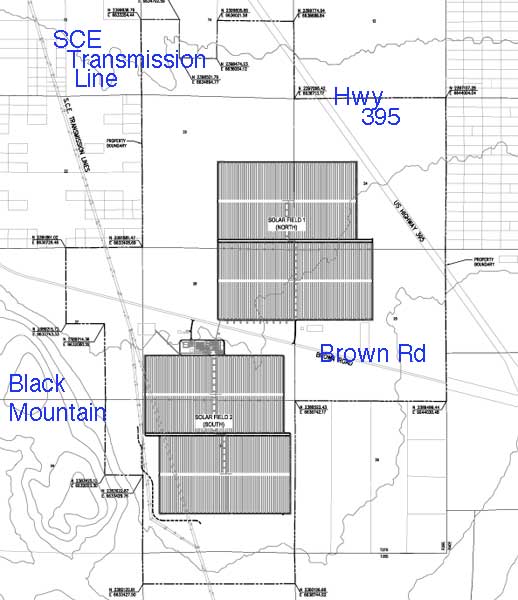

A transmission line tie-in would be with the 230 kilovolt Southern California Edison (SCE) Inyo-Kern/Kramer Junction transmission line using a new line 2,610 feet long, all on site.

Solar Millennium hopes to have the decision from CEC by September 2010, and go online by July 2013. But many obstacles stand in their way. Because of the aggressive Fast-Tracking schedule that both CEC and BLM are being forced to follow, many feel that public concerns are not being given an adequate hearing.

The project will cost an estimated $1 billion to construct. It is a Fast-Tracked project, trying to make a December 31, 2010, deadline to qualify for an American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grant to cover 30% of the cost. The company is also applying for a Department of Energy loan guarantee.

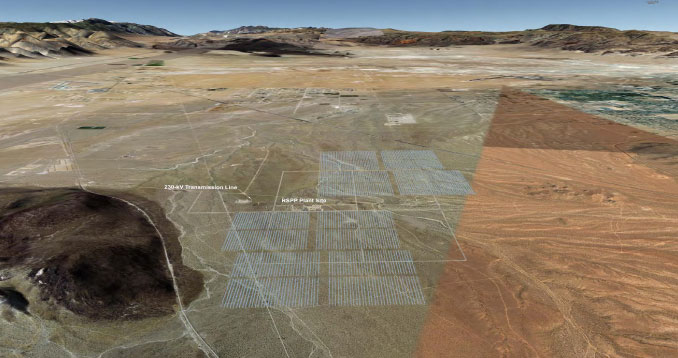

^Digital construction of what the original Project footprint would look like across the Indian Wells Valley. The city of Ridgecrest lies to the right, the Sierra Nevada to the left, and the Coso Hills in the center distance. Owens Valley begins at the gap in the upper left.

(From the Application for Certification on California Energy Commission website http://www.energy.ca.gov/sitingcases/solar_millennium_ridgecrest/documents/applicant/afc/)

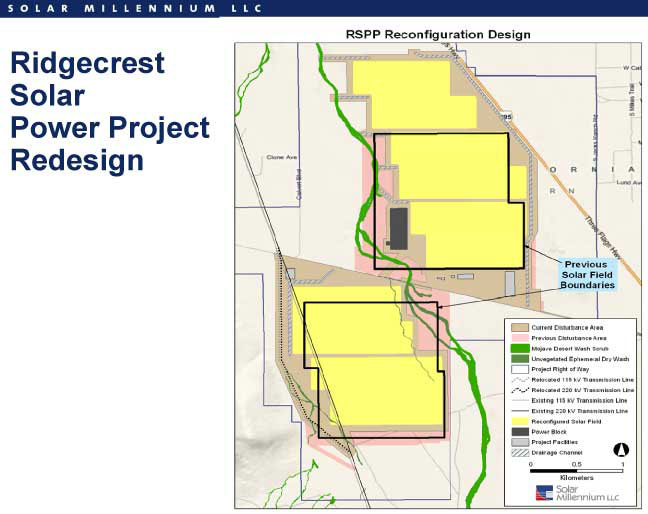

^The plant was redesigned after hydrologists pointed out that redirecting floodwaters in El Paso Wash would be expensive and light not work. The new plan has the solar field avoiding the ephemeral wash.

(From http://www.energy.ca.gov/siting/meetings/2010-01-22_meeting/presentations/).

^Original design, showing topography and roads.

(From the Application for Certification on California Energy Commission website http://www.energy.ca.gov/sitingcases/solar_millennium_ridgecrest/documents/applicant/afc/)

(From http://www.energy.ca.gov/siting/meetings/2010-01-22_meeting/presentations/).

Project facilities. (From the Application for Certification on California Energy Commission website http://www.energy.ca.gov/sitingcases/solar_millennium_ridgecrest/documents/applicant/afc/)

(From http://www.energy.ca.gov/siting/meetings/2010-01-22_meeting/presentations/).

Surface Hydrology

The primary wash on site (El Paso Wash) is composed of several washes varying in width from 10 to 40 linear feet across interspersed between upland areas within the disturbance area. Two smaller ephemeral washes are located within the western portion. A total of 16.6 acres of Jurisdictional Waters are present (which must be mitigated). In the original plan the washes that cross the disturbance area generally from south to north would be rerouted into three channels along the east and west sides of the disturbance area and into realigned channels (see map, which also shows the original water line to a new ell next to Ridgecrest).

When we arrived at the December 15, 2009, CEC workshop in Ridgecrest, a BLM hydrologist was explaining to Solar Millennium that this plan was not going to work. The 1984 flood event here almost destroyed Highway 395, and $10 million of damage was done on base in the Inyokern flood. Channelizing the wash with cement and riprap would only make floodwaters go faster through the Project site.

The natural form is for a large floodplain to dissipate energy, and flooding has been a problem in the area. The hydrologist recommended planning for a 100-year flood event. Higher peak flows would overtop the flood control structure, she said. These systems are dynamic, and may change course and flow in different areas. Decisions should not be made without walking the site (something Basin and Range Watch always recommends) Alluvial fans have uncertain flow paths. How do you guarantee stability of the engineering? Do not rely on models too much, the hydrologist added.

Don Decker, long-time resident of Ridgecrest, commented that he was dumbfounded the magnitude of the material was moved by the 84' flood. It would have flooded out the project, he said. El Paso wash flowed strongly, changing the channel, uprooting creosote -- mitigation can not be found for this. "For your own benefit you should be aware of the risks, How you can possibly think of investing a billion dollars in this is beyond me" he ended.

CEC Project Manager Eric Solorio (who is also handling the Ridgecrest Solar Millennium case) pointed out that the nearby proposed Beacon Solar Energy Project to the west in Kern County was going to go to considerable expense to have drop structure channelization on Pine Tree Creek. "Best to avoid the wash," he said.

California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) is actively developing guidance on arid stream channels, but is finding conflicting delineations with other groups such as the consultant community. For example, what plants would indicate a wash? Nobody is clear on how to delineate desert streams. This is not just an ecosystem value but might be critical to determining setbacks. (It was mentioned that this problem should not hinder the need to keep on schedule.)

^California Energy Commission workshop in Ridgecrest community center, December 15, 2009.

^El Paso Wash, a broad dry sandy channel. Ridgecrest residents have seen it flood.

Big Groundwater Concerns

In this critically-overdrawn desert basin, any pumping of groundwater for dry-cooling the plant and dust control is a great impact. Many local residents stood up to spoke at the meetings about this contentious topic. Concerns inlcuded residents living next to the Project having their well water levels potentially lowered and that drinking water supply was going to handed over to an industry. The basin has been in overdraft since 1960 and has gone down every year, according to knowledgeable long-time local residents. Many wells are in trouble. The water district has explored exporting water from the Central Valley Project, but that is 50% over-bought. They have also looked into desalinization, but that would be high-dollar water.

"To use potable water is unacceptable," said Don Decker. "Our groundwater is water in a bank for our future. We're mining water."

Judy Decker, who had been on the local water board, commented that there was 30,000 acre-feet of water use in the valley and only 7 acre-feet of recharge.

CEC staff responded that surely there existed a solution to this problem.

Cultural Resources

Public comments were made by various Tribes such as the Kawaiisu that have an interest in the Project area. The valley area is rich, and Black Mountain is a sacred area still.

Biodiversity

The area is also biologically rich from basaltic soils weathered from nearby Black Mountain that provide abundant nutrients. The fan has spectacular wildlife and spring wildflower shows.

Desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) - Federally and State Threatened.

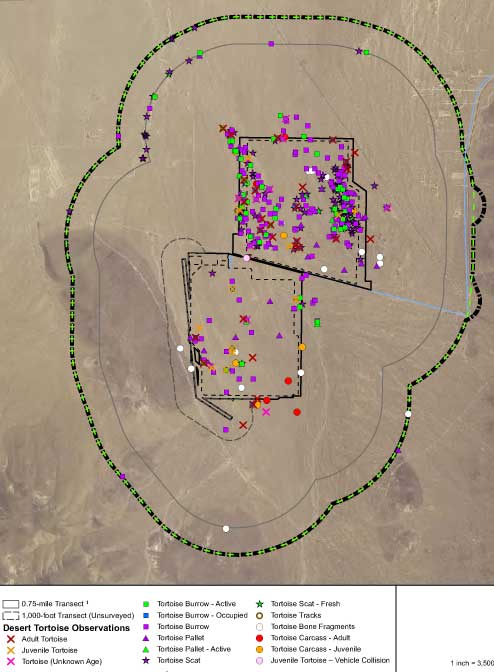

According to the Application for Certification, tortoises were observed during surveys in spring 2009, 40 of which were within the disturbance area. Twenty-two occupied burrows and 48 burrows with sign of recent use were also found. Based on survey results, 69-70 adult desert tortoises are estimated to occur in the disturbance area, or 9.8 tortoises per square kilometer.

This is a higher density than recently reported within the nearby Fremont-Kramer Desert Wildlife Management Area (with 5.3 to 7.6 tortoise per square km). The Project site occurs within the desert tortoise West Mojave recovery unit. Movements between local populations are important for long-term population viability, and the Project site could contribute to population connectivity with known populations to the south. Due to its overall large size, the proposed Project could contribute to a potentially significant loss of suitable habitat available dispersal between local populations.

Seldom have we seen Energy Commission biologists so concerned about the biological impacts as for this project. CEC biologist Dick Anderson emphasized the high density of tortoises estimated to occupy the site -- higher than Ivanpah Valley.

^Desert tortoises and sign found on the Project site (Map from workshop).

^I photographed this tortoise in seemingly poor, drought-ridden habitat near California City. What humans think is poor habitat may not match what the tortoise prefers.

Western burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia) - California Department of Fish and Game Species of Special Concern, BLM Sensitive Species.

Seven active burrows were located in three separate regions of the Project site including five main or nest burrows and two satellite burrows. A minimum of 8 burrowing owls were found, including at least two nesting pairs with juveniles.

Moving owls involved plugging their burrows to force them to move, but in projects of this size, the normal distance of movement to find a new home range is smaller than the project footprint, pointed out CEC biologist Dick Anderson.

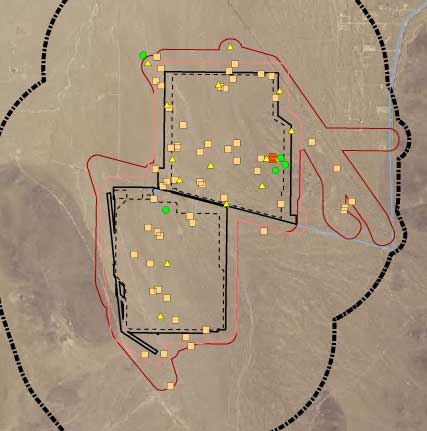

<Burrowing owls and sign. (Map from workshop).

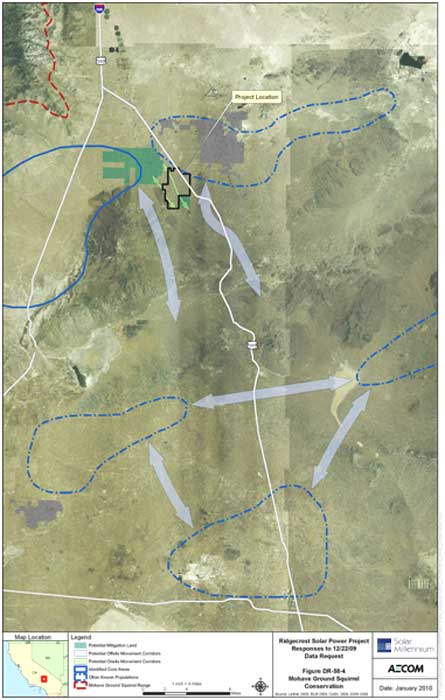

Mohave ground squirrel (Spermophilus mohavensis) - State Threatened.

High-quality habitat for this endemic west- and central-Mojave ground squirrel includes a diversity of shrub species, native herbaceous plants, and sandy or loamy soils that provide

High-quality habitat for this endemic west- and central-Mojave ground squirrel includes a diversity of shrub species, native herbaceous plants, and sandy or loamy soils that provide

suitable substrate for burrow digging. They were not detected within area, but suitable habitat is found, including some high-quality habitat. It is expected to occur. There have been 24 detections within 5 miles of the site, more to the north, outside of the MGS conservation area. 234.7 acres of high-quality habitat occurs in the site and buffer area. A total of 1,725.6 acres of potentially suitable habitat occurs. The core Mohave ground squirrel population lies southwest of Inyokern, and another population occurs to the east of Ridgecrest. Due to its overall large size, the proposed Project could contribute to a potentially significant loss of suitable habitat available for dispersal between local populations.

<Mojave ground squirrel connectivity areas, arrows showing potential movement corridors. Solid blue line areas indicate identified core areas; dashed lines are other known populations. Blackline indicates Project site. Green shaded area is possible mitigation land. (From: Ridegcrest Solar Power Project [09-AFC-9] CEC Staff Data Request Numbers 53 - 78 Technical Area: Biological Resources [AFC Section 5.3] Response Date: January 25, 2009)

It is impossible to move ground squirrels from this good area, noted Dick Anderson.

Explore Mojave ground squirrel West Mojave habitat >>here.

Other Sensitive Species found during 2009 surveys by the Applicant:

Loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) - CDFG Species of Special Concern.

Le Conte’s thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) - BLM Sensitive .

American badger (Taxidea taxus) - CDFG Species of Special Concern.

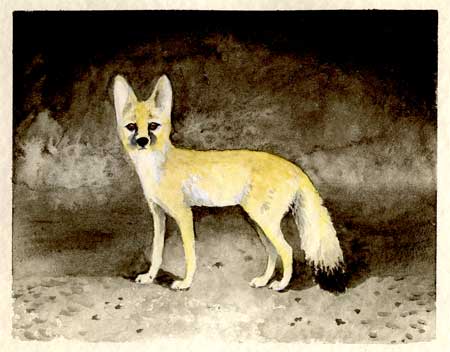

Desert kit fox (Vulpes macrotis arsipus) Calif. Code of Regulations PFM . Burrows and scat were commonly observed throughout the area during spring 2009 surveys. A total of four active kit fox burrows/complexes were detected within the disturbance area.

>Watercolor sketch of kit fox caught in night light (Copyright Laura Cunningham).

Nelson’s bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) - BLM Sensitive. Bighorn sheep have been reintroduced to China Lake NAWS, 15 miles east-southeast. Although not seen during surveys, we have seen sheep cross valleys and basins to migrate to new mountain ranges, and they will come down to upper alluvial fans to feed, especially when wildflowers are lush. But presently no bighorn occupy the nearby El Paso Mountains.

Birds Detected During Surveys:

Black-throated sparrow, Common raven, Verdin, House finch, Mourning dove, Rock wrens

Greater roadrunner, Horned lark, Sage sparrow, Lesser nighthawk, Costa’s hummingbird, Brewer’s sparrow, White-crowned sparrow, Yellow-rumped warbler, Blue-gray gnatcatcher, Tree swallow, Cliff swallow, Great-tailed grackle, Pine siskin, Red-tailed hawk, Turkey vulture, Swainson's hawk, Yellow warbler, Vaux’s swift, Yellow-headed blackbird.

<Sketch of Swainson's hawks in migration. ^Rock wren.

Mammals noted during surveys:

Coyote (Canis latrans) dens and sign were detected throughout the site.

Bobcat (Lynx rufus) scat was observed in the large granite boulder outcrops in the central-eastern portion of the site.

Black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus) desert cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii).

Kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spp.) and pocket mice (Perognathus spp.) are abundant.

White-tailed antelope squirrel (Ammospermophilus leucurus).

Desert woodrat (Neotoma lepida).

Wild burro (Equus asinus) scat was present on site. (Many residents point out that these animals are undesirable for the desert ecosystem.)

Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) could occur.

Special-status plant species potentially occurring on the site:

Red Rock tarplant (Deinandra arida, syn. Hemizonia a.)

Mojave tarplant (Deinandra mohavensis, syn. Hemizonia m.)

Alkali mariposa lily (Calochortus striatus)

Brown fox sedge (Carex vulpinoidea)

Muir’s tarplant (Carlquistia muirii, syn. Raillardiopsis m.)

Gilman’s goldenbush (Ericameria gilmanii)

Hall’s daisy (Erigeron aequifolius)

Red Rock poppy (Eschscholzia minutiflora ssp. twisselmannii)

Creamy blazing star (Mentzelia tridentata)

Sweet-smelling monardella (Monardella beneolens)

Charlotte’s phacelia (Phacelia nashiana)

Sweet-smelling monardella (Monardella beneolens)

Charlotte’s phacelia (Phacelia nashiana)

Nine-mile canyon phacelia (Phacelia novenmillensis)

Latimer’s woodland gilia (Saltugilia latimeri)

Cacti found in site and buffer area: Silver cholla (Opuntia echinocarpa), Beavertail prickly pear (Opuntia basilaris), Mojave fish-hook cactus (Sclerocactus polyancistrus), and cottontop cactus. Mojave fish-hook cactus is listed by California Native Plant Society as a watch list species and three plants were found in the southwest portion of the buffer survey area. One species targeted by the BLM, cottontop cactus (Echinocactus polyancistrus), was observed; three specimens of this species were located in the eastern portion of the disturbance area and one specimen which was located near these individuals within the buffer.

^Thistle sage (Salvia carduacea).

Plant Communities

Mojave Desert Wash Scrub: Scale-broom (Lepidospartum squamatum), Creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), Spiny senna (Senna armata), Cheesebush (Hymenoclea salsola), Bursage (Ambrosia dumosa), Virgin River brittlebush (Encelia virginensis), and Rayless goldenhead (Acamptopappus sphaerocephalus). Herbaceous plants include California desert dandelion (Malacothrix californica), Fremont pincushion (Chaenactis fremontii), Distant phacelia (Phacelia distans), and Wallace eriophyllum (Eriophyllum wallacei).

Mojave Creosote Bush Scrub:

Creosote bush, burroweed, cheesebush, and Virgin River brittlebush. Common herbaceous species include redstem stork’s bill (Erodium cicutarium)(Introduced), Mediterranean grass (Schismus sp.)(Introduced), Needle goldfields (Lasthenia gracilis), and Blue dicks (Dichelostemma capitatum).

A large volcanic outcrop occurs along the western edge Parish’s larkspur (Delphinium parishii ssp. parishii), Snake’s head (Malacothrix coulteri), and Dwarf cottonrose (Logfia depressa). In the central-eastern portion of area a large granite boulder outcrops occur with Desert bricklebush (Brickellia desertorum), Eastern Mojave buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum var. polifolium), and Cooper’s goldenbush (Ericameria cooperi).

^(Left) New leaves on Wolfberry (Lycium andersonii); (right) Spiny senna (Senna armata). Both on southern Project site.

County Impacts

One member of the public asked how much estimated taxes Solar Millennium would pay to Kern County? Would the amount be cut in half because this is an energy project? CEC pointed out that the assessment value will not be assessed like other industries. The questioner continued: will this affect taxes in the county? Hector Villalobos, BLM Ridgecrest Field Manager, answered they did not know.

We have heard from other officials in other counties that the increased fire protection, road up-keep, and stresses on other services may cost millions of dollars.

Private Land Alternative?

Most solar companies seeking to build largescale projects do not want to go to the "trouble" of seeking and purchasing private land. The argument goes that there is not enough time to aggregate a large enough parcel. Of course, if artificially expedited federal and state deadlines were removed this would not be a hindrance.

At the December workshop a local man made a public comment he said he realized the cost might be higher to buy private land. "But looking into the problems I've seen today, it might be more cost-effective than leasing public land." Many other local people hoped CEC would look into private land alternatives because of the biological, cultural, and other riches of the site.

CEC staff said only one alternative was being considered (as of December 2009), the Arcero Ranch by Koehn Lake, a private parcel. "If we considered every alternative out there we would have a 10,000-page document," Solorio stated.

Hector Villalobos, BLM, explained that originally the Project had a much larger footprint and had been located to the north by the city dump (which we note would have also placed it right next to residences). He said BLM had concerns of such a huge project close to town, and asked Solar Millennium to move it and reduce the acreage.

Solar Millennium said it did not want to seek any alternative sites. Scott Galaty, counsel for the company, said years ago the state had considered a "really big area" clumped together for solar projects, instead of smaller projects dotted all over. Then that direction got reversed when more solar applications came in. Originally Solar Millennium sought two sites: 8,000 acres here and 13,000 acres at Sage Canyon. BLM asked them to pull back on the Sage Canyon site due to the high density of Mojave ground squirrel. They looked at the dump area, but it had even more washes than the present choice, and the triangle created by highway 395 made the site too small.

See Mojave Desert Blog for a discussion.

Cumulative Impacts

Renewable projects proposed on BLM lands in the West Mojave Plan area alone include

approximately 250,000 acres of solar projects, and another 400,000 acres of wind energy projects. Further impacts to scarce water resources and wildlife connectivity corridors will occur if build-out is allowed.

^A crowd gathers at Ridgecrest for the January 5, 2010, workshop,site visit, and informational hearing.

^People examine Solar Millennium's maps of the proposal.

^El Paso Mountains Wilderness Area lies beyond these foothills to the southwest of the Project site, just beyond the one-mile buffer.

^Silver cholla on the northern Project site, with the Sierra Nevada in the background.

^The southern site in March, a green field. The transmission line Solar Millennium wants to interconnect with passes along the background hills.

Evening primrose (Camissonia) rosettes emerging in early March.

^Brodiaea (probably Dichelostemma pulchellum) leaves coming up after the rains of 2010, on the Project site.

^Panorama of the Project site looking northwest toward the Sierra.

^A well-kept camp site in the southern Project area. On every visit we have made here we have seen many recreationists using the site.

^2005 bloom of Desert dandelion and Pincushion to the north of the Project site.

^The southern site, February 2010.

^Sunset over the Sierra from near California City.

References:

Romero-Alvarez, Manuel and Eduardo Zarza. 2007. Concentrating Solar Thermal Power. In, Frank Kreith and D. Yogi Goswami (eds.), Handbook of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. CRC Press: Boca Raton, London, New York.

Some Ridgecrest links:

The Daily Independent, Ridgecrest, CA

All photographs and artwork Copyright 2010 Laura Cunningham unless otherwise stated.

HOME.....Solar Millennium Amargosa Valley.....Mojave Ground Squirrel