Industrial Solar Energy Developments Threaten Desert

February 15, 2009 - Ivanpah, California

UPDATE! April 16, 2009 >>here

We stood in the quiet fan sloping gradually down from snow-covered Clark Mountain on the border of the Mojave National Preserve. The winter day was brisk and breezy, the air fresh, and the creosote bushes were green from recent rains. I noticed many animal tracks in the sandy washes winding through the cactus and bursage: coyotes, bobcats, kangaroo rats, kit foxes. Small green rosettes of annual wildflowers poked their leaves upwards, a harbinger of the coming spring when their blooms would add color to this desert.

Meanwhile in the distant city, other folks had designs on this land. Plans were being made, investments sought, deals struck. On February 11, Southern California Edison agreed to purchase 13,000 megawatts of electricity from solar projects to be built by Oakland-based BrightSource Energy. It was the largest solar electricity deal in the world. BrightSource has been busy during the past two years undergoing the long application process to gain control of nearly 4,000 acres (about 6.4 square miles) of public land near the Nevada border in order to build a 400 megawatt (MW) solar thermal "power tower" plant, the first stage of the deal.

Here would be the so-called Ivanpah Solar Energy Generating System (ISEGS).

^Ivanpah Valley before.

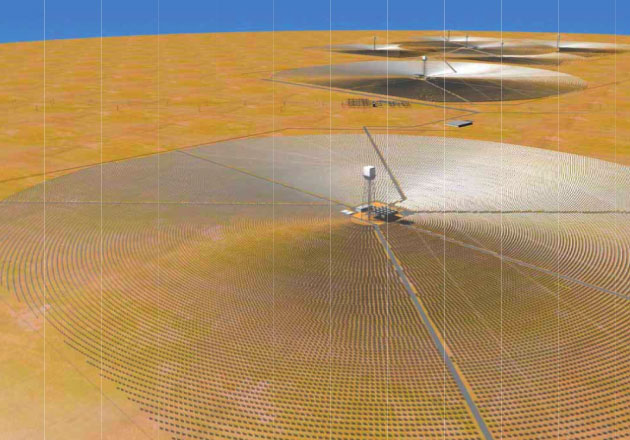

^After?

The Preliminary Staff Assessment (PSA) describing the project, prepared by the California Energy Commission, dryly notes: "The ISEGS site would be located in an undeveloped area. Brush would be cleared prior to grading."

"Implementation...would result in extensive grading and removal of existing desert soils, resulting in the potential for increased erosion and offsite sedimentation." This grading would take five months.

After the desert habitat is completely removed with large scraper machines, and the site is "cut and filled" [see update on this >>here] 318,000 heliostat mirrors would be placed in curving rows aiming the sunlight up to boilers located on centralized 459-foot tall power towers. Each mirror would track the sun throughout the day and reflect the solar energy to the receiver boiler. In each of the 5 plants, one Rankine-cycle reheat steam turbine would then receive the steam from the solar boilers to turn turbine generators (for more on how concentrated solar power works see >>here). Herbicides would then be regularly sprayed, according to the PSA, to keep weeds down and prevent fire-fuel build-up.

Administrative and maintenance buildings, a warehouse, detention ponds, and even a small sewage system would also be built on-site, and small amounts of hazardous wastes produced that "contain mercury, lead, cadmium, copper, and other substances hazardous to human and environmental health." In other words, this will be an industrial site, not a "green" project.

^Digital image of the proposed Ivanpah solar power plant showing the 5 mirror arrays around the 7 power towers. (From the pdf file ISEGS PSA)

^This view will be sacrificed for the solar power tower arrays, with the steam turbine generators hooking into the transmission line in the distance.

The PSA states the project will create 90 jobs and people will have to commute one hour each way. Will these people be required to drive electric cars? This does not really help reduce green house gases.

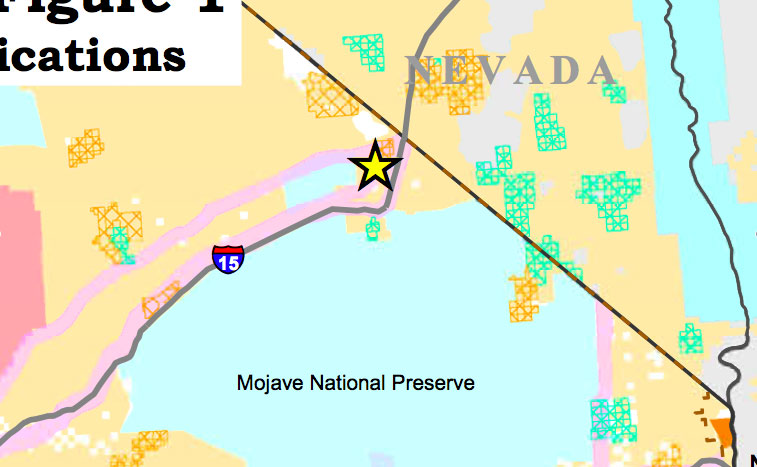

^The star indicates the location of the Ivanpah solar project in San Bernardino County, California. Yellow polygons are more proposed solar power developments in the desert, and green are proposed wind projects. (From the ISEGS PSA.)

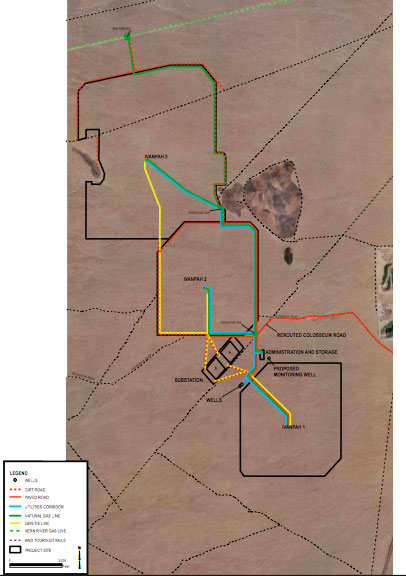

^The "footprint" of the Ivanpah solar project is huge over undisturbed desert. Note the small hill to the right of the project, which we dubbed "Ferocactus Hill" from its many succulents. It is visible in many of our photos. (From the ISEGS PSA.)

^"Ferocactus Hill" with barrel cactus.

The locations of subsequent solar generation projects are yet to be chosen, but would theoretically be completed in stages by 2016, with Ivanpah set to open by 2013. BrightSource wants a total of 10,500 acres of public land run by the Bureau of Land Management. The company plans to sell 300 MW of power from the Ivanpah solar plant to Pacific Gas & Electric, and the remainder to Southern California Edison. (See the story in the Los Angeles Times >>here.)

The proposed project represents part of the efforts by some to sacrifice over one million acres of public lands and arid lands ecosystems in California alone to questionable "green" energy projects. The scope of impacts and environmental devastation that will result from these projects are not worth the amount of energy, that could instead be generated from urban rooftop photovoltaic panels (see our story on this >>here).

^Barrel cactus on the project site.

BrightSource raised more than $160 million from equity investors including Google.org, VantagePoint Venture Partners, and Draper Fisher Jurvetson, but they will need billions of dollars more to develop the full 13,000 MW worth of power plants. Edison will not admit how much it is paying for the solar-generated power, but did say that the electricity from the first Ivanpah plant will be priced below the state benchmark known as the Market Price Referent, 12.5 cents a kilowatt-hour. We guess that the cost to generate the electricity from the solar thermal plant would be just under this figure. Natural gas costs 4.7 cents per kilowatt-hour to generate.

BrightSource probably chose the Ivanpah site partly because it is right across the valley from the Bighorn Generating Station, a 598-megawatt natural gas-fired, combined-cycle power plant located near Primm, Nevada, approximately 35 miles south of Las Vegas. The Ivanpah solar project will need natural gas too in order to keep the start-up boiler warm during cloudy days and cold mornings. Natural gas for the project would be obtained by a new 5.3-mile long natural gas pipeline connecting to the Kern River Gas Transmission Line, less than a half a mile to the north of

the project site.

^Natural gas-fired power plant in Ivanpah Valley within view of the project site.

^Buckhorn cholla on the project site.

^Clark Mountain in Mojave National Preserve, as viewed from the middle of the Ivanpah solar power proposed site.

^Pencil cholla protects itself well with long spines.

^Pencil cholla, Silver cholla, Creosote, and Bursage on the project site. This habitat will have to be completely scraped to build the power system.

^Mojave yucca on the project site.

^Beavertail cactus.

Rare Plants and Desert Animals

The project will make a significant impact to the overall diversity of life in the Mojave Desert. The PSA admits there is really no way to compensate for the loss of most of the rare plants that are listed. Most of the mitigation measures are to “protect and enhance offsite populations or some other form of compensatory mitigation.” What will happen to succulents, yuccas and Joshua trees that are displaced? Will they be moved, sold for landscaping or destroyed? It is our opinion that the PSA has been written prematurely. The PSA should be updated after mitigation measures are thought out and given time to be reviewed by the public.

At least 12 rare plants have been found on the project site, some with significant portions of their range facing destruction from the solar facility. The Rusby's desert mallow, for example, has been described by the California Native Plant Society as "rare, threatened, or endangered in CA and elsewhere." Their map lists only 35 locations that the plant has been found, all in California, and clustering around the Clark Mountain area.

A diverse range of insects, reptiles, birds, and mammals also dwell on this desert fan.

^We found this butterfly in spring. It is a California patch (Chlosyne californica), and its host plants is the shrub Goldeneye (Viguiera parishii).

^A Desert iguana in Ivanpah Valley, April 2009.

^Desert horned lizard.

^Sidewinder in Ivanpah Valley.

^A Western banded gecko hunts insects at night on the desert floor.

^A LeConte's thrasher walks amid shrubs.

^A Sage sparrow sits on a winter-leafless Catclaw acacia.

^A kangaroo (Dipodomys merriami) rat in Ivanpah Valley.

^ We found a Bobcat track leading across the project site.

Desert Tortoise Habitat

The project site looks to us to be excellent habitat for the Federally Threatened Desert tortoise. The Ivanpah PSA says, "the 2007/2008 protocol desert tortoise surveys found 25 live desert tortoises, 97 desert tortoise carcasses, 214 burrows, and 50 other tortoise sign."

The finding of 97 desert tortoise carcasses may indicate a problem with respiratory disease or possibly some other impact. How can a project that destroys so much habitat for this species be considered when such a die off is noted? A line distance sampling survey should be conducted during activity seasons for the next couple of years before approval of this project is considered.

Since tortoises cannot co-exist with solar thermal mirror arrays, what usually has to happen is that the tortoises are "cleared." This involves removing and translocating ALL tortoises from the entire 4,000 acres. All burrows are dug up to try to find animals underground. Often many are missed, so several "clearances" must be carried out. The applicant company has been required to "mitigate" this damage by acquiring desert land somewhere else and translocating all the tortoises found and dug up to the new site. So far the requirement has been to buy land in a 1:1 ratio of land destroyed for the project, but the San Gorgonio chapter of the Sierra Club has sent a letter advising this to be a 5:1 ratio.

But even with this plan, mortality for translocated desert tortoises has been high. The PSA states that an estimated 15 percent is "normal." But recent experiences with the Fort Irwin translocation operation suggest that even higher mortality rates are probable. Drought only exacerbates the stress of moving tortoises from their home ranges to unfamiliar new areas, where they have to compete for food and burrows with already present tortoises. Many of the Ft. Irwin translocation tortoises disastrously were predated by coyotes. Walking around the translocation site near Primm, Nevada, where thousands of tortoises were translocated from the Las Vegas Valley boom developments, we see many shells lying on the ground. Mortality rates may be closer to 50%.

^Tortoise shell bleaching in the desert sun at a translocation site.

Where will mitigation land be bought? [Update - tortoise translocation plan >>here] Will all tortoises be placed on the same mitigation land? Will follow-up studies be carried out to determine the success of translocation and survival? How will coyote and other predation be prevented on translocated tortoises? The PSA says the applicant will "develop a Desert Tortoise Translocation Plan" - this should be finished before the Ivanpah project is approved.

The PSA also states that "raven management" will take place. Ravens sometimes predate juvenile tortoises, especially when human activity attracts the birds with trash and food scraps. What kind of reduction measures would be taken to minimize raven predation on tortoises? If native predators are to be exterminated, the PSA needs to explain how this will take place. Will the same measures apply to coyotes on the translocation site? The PSA should be able to describe and admit the unattractive details that will need to be implemented for predator reduction. These details should not be green-washed.

^An Ivanpah Valley tortoise wanders it desert home.

^A tortoise burrow.

^A tortoise just emerged from its burrow, still covered with dirt.

^The Ivanpah project site is excellent tortoise habitat.

^Scraped tortoise habitat for new development in the Mojave Desert of Kern County.

^Biologists set up small tortoise exclusion fences to keep the animals from being crushed by machinery during construction. This is what will happen to Ivanpah tortoise habitat for the solar development.

^Barrel cactus at the edge of the project site.

Water

Ivanpah Valley is part of the Mojave Desert, an area that receives 2 to 10 inches of rain each year. Groundwater in each basin is often "fossil water" that has built up over thousands of years. I talked to a geologist once who told me to think of groundwater in the desert like gold, that it could be "mined" like a mineral, and that if it was mined too much, it could all be taken. Water in these basins does not recharge fast enough to keep pace with large-scale pumping.

The Ivanpah solar project PSA states that during construction, an average of 99,333 gallons per day for Ivanpah 1 and 2 and 194,000 gallons per day for Ivanpah 3 would be used, with up to an additional 47,000 gallons used during pipeline hydrotesting. This would be about 76 to 149 acre-feet per year.

During grading of the second and third phases of the project, dust would be generated that may result in the need for more frequent washing of the existing heliostats. This heliostat washing could result in an additional 50 acre-feet per year of groundwater use. After this, as a part of routine operation, the mirrors would be washed with a spray every two weeks. This would amount to about 100 acre-feet per year. The PSA says, "over the next 50 years, the use of the...groundwater is expected to increase and,

along with that increased use, the overdraft in the sub-basin is expected to become greater. The project’s pumping of groundwater alone would contribute to this overdraft...."

We believe the project does not justify pumping even more water in an arid region, possibly resulting in the death of deep-rooted shrubs and small wash trees such as Catclaw acacia in the future.

^Clark Mountain viewed from the Ivanpah solar project site.

^Calico cactus.

Transmission lines

^A 115 kilo-volt powerline crosses the middle of the Ivanpah project site.

The ISEGS project would be interconnected to the Southern

California Edison grid by three new 115-kV transmission generation tie lines. In order to transmit the full generation load projected for the ISEGS

project and other planned electric generation projects, 36 miles of the existing 115-kV transmission line would need to be removed, and a new double-circuit 230-kV transmission line between the Eldorado

Substation in Nevada and the proposed new Ivanpah Substation in California put in. Another transmission line would be upgraded to the Mountain Pass substation to the south of the project.

^Silver cholla.

Views

^The view from Mojave National Preserve, looking northwest toward the fan where the Ivanpah solar project will spread. The small dark hills locate the site.

^A digitally-created view of what the Ivanpah solar project would like like as viewed from the lower slopes of Clark Mountain. looking northeast. (From the ISEGS PSA)

^View from the "Ferocactus Hills" looking southeast across Ivanpah Valley toward the ranges within Mojave National Preserve on the right horizon. Much of the middle-ground creosote flat would be destroyed for the project.

^Backlit Buckhorn cholla on the Ivanpah solar project site.

The evidence is clear that none of these projects is necessary to meet renewable energy goals. We can generate more renewables that are truly clean on our rooftops without killing one plant or animal, without scraping one square foot of soil. Ivanpah is a peak power proposal, not base load. Not one coal plant will be replaced by Ivanpah CSP. The alternative could be to put 2.5 kilowatts of photovoltaic panels on the 160,000 homes the project applicant claims it will serve. Watt for watt!

See the Alliance for Responsible Energy Policy >>here for more on how to help develop localized renewable energy such as rooftop solar.

See also the Desert Protective Council 'Desert Blog' >>here for more great information on what is happening to our deserts.

See more fantastic desert stories at Coyote Crossing by Chris Clarke >>here. Check out the beautiful poster "Ivanpah Valley: Worth more than megawatts" >>here.